Jimi Hendrix was a one of a kind musician who revolutionised the guitar. Although he is often best remembered for his incendiary solos and lead work (and rightly so), his rhythm playing style was no less innovative and influential.

Like a scientist having a new species or planet named after them, Jimi Hendrix was such a legend in popular music that he has a chord nicknamed after him.

In this article we explore the chord — the heavy and chaotic yet colourful and bluesy sound from classic songs like Purple Haze and Voodoo Child — that has become known as the Hendrix Chord.

The Hendrix Chord

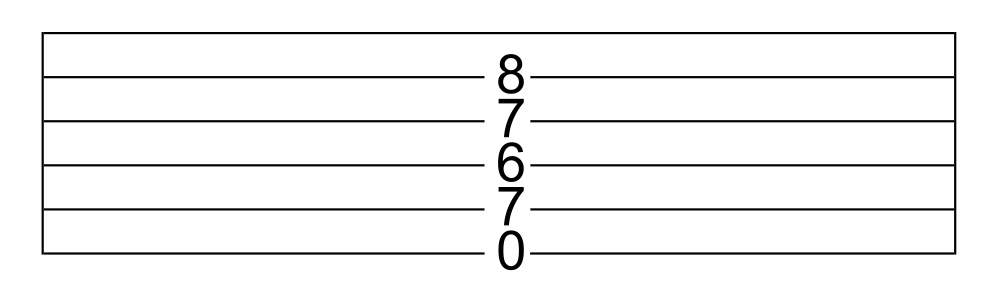

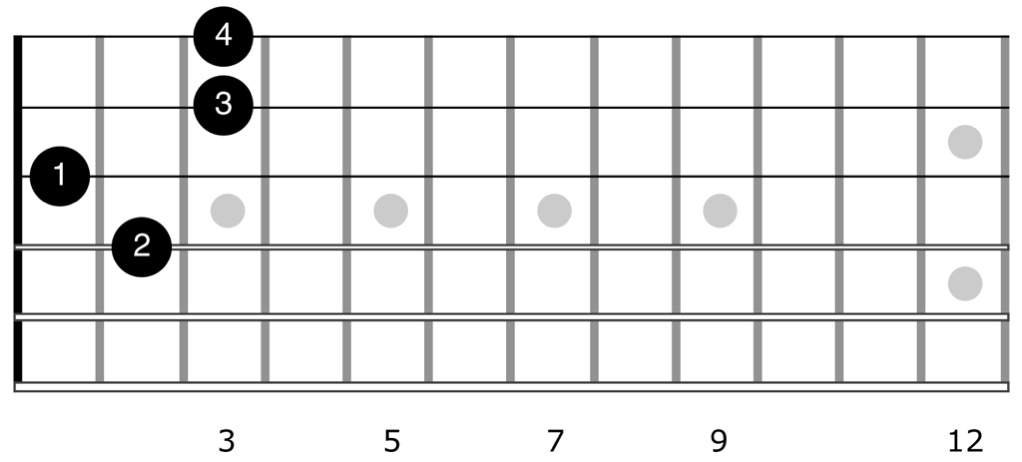

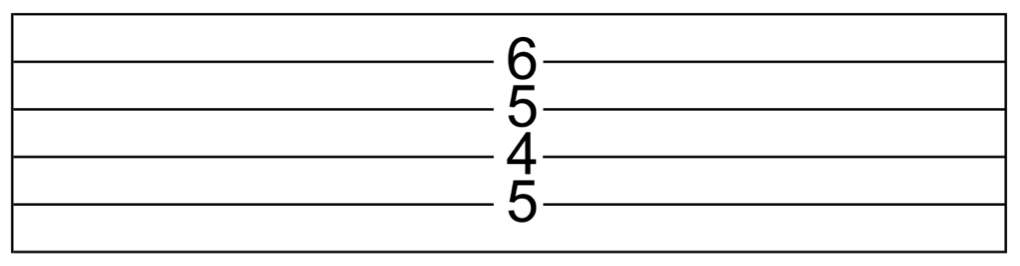

The classic Hendrix Chord is properly called E7#9 (or technically Eb7#9, since Hendrix tuned a semitone flat on most recordings). Here is what it looks like on guitar:

(When playing E7#9, Hendrix would also let the low open E string ring through to make it sound bigger. This is displayed in the tab above).

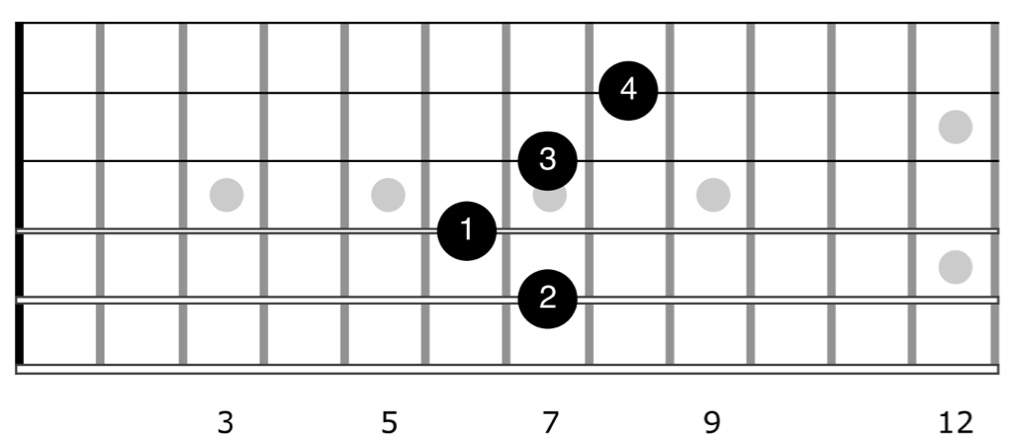

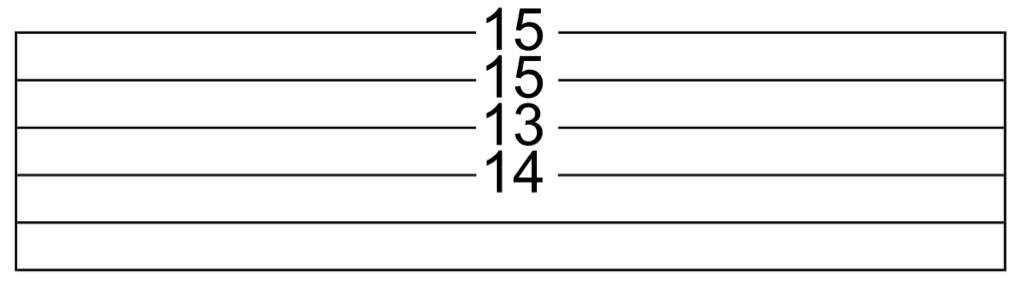

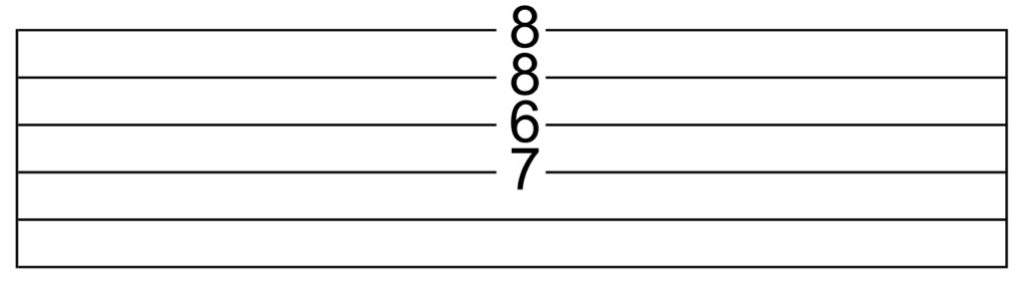

Like any chord on guitar, it’s possible to imply E7#9 in many different ways, but another popular shape that you will see used often is this:

This is a very cool shape for E7#9 because it can be easily moved up twelve frets, giving you twice the options with one shape:

You can hear both of these shapes in “Cold Shot” by Stevie Ray Vaughan, one of Hendrix’s many musical descendants:

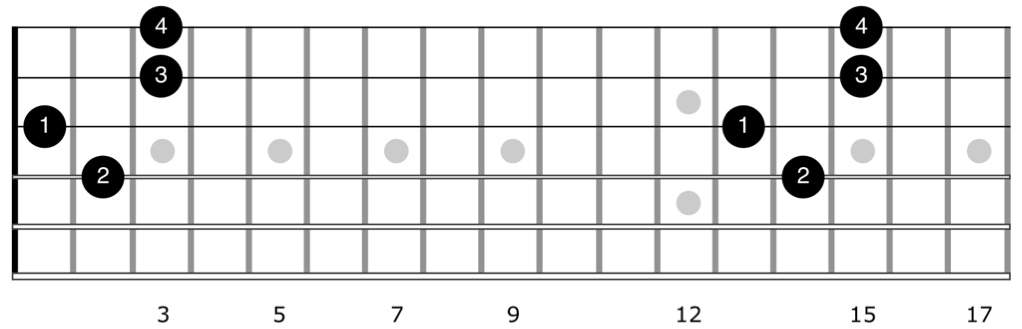

When it comes to this shape, you might find it faster, easier and more comfortable to barre the top two notes with your pinky finger:

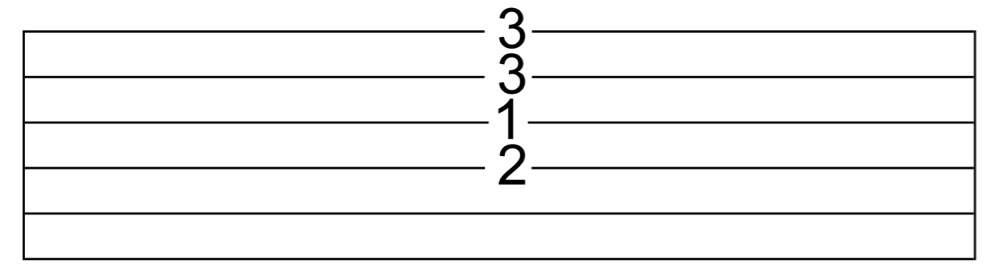

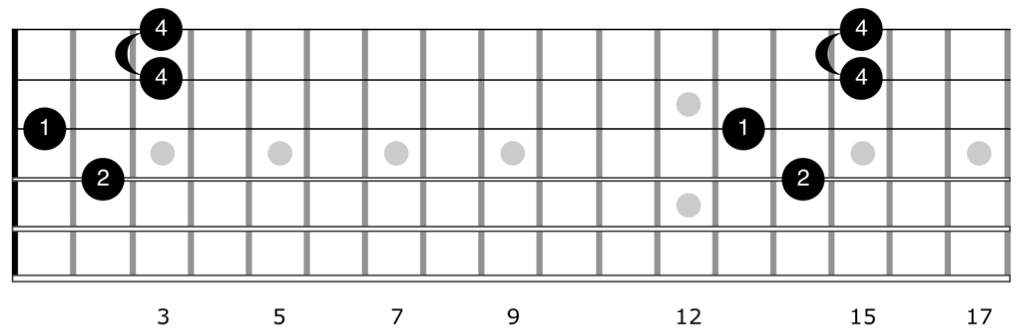

Both of the 7#9 shapes above are moveable, so you can use it to play any 7#9 chord by moving it to the desired note just like you would any barre chord. For example, D7#9 using the first shape would be this:

Or here’s an A7#9 being played using the second shape:

Now that you can see what it looks like and have a few ways to play it, your next question might be – but what is it? What’s special about it, and why does it sound cool?

The Music Theory behind the Hendrix Chord

I’m going to explain the theory and try my best to make it interesting and informative, but not over-complicated if you don’t have much experience in music theory. Hopefully you will still pick up some important things even if you don’t know any theory.

As I mentioned at the start, the proper musical name of the Hendrix Chord is the 7#9 chord. Jimi Hendrix popularised its sound, but he was not the first person to use it, and he certainly didn’t invent it.

The 7#9 is a known chord type, and its name has two separate parts that tell us what is actually in it – 7, and #9.

In order to explain what is so special about this chord, we need to understand the foundation it is built on — the 7th chord.

It all starts with seventh chords

Dominant 7th chords, simply referred to as 7 or 7th chords — such as E7, B7 G7, D7, A7, etc. — are kind of special in music, because they contain both major and minor elements.

A 7th chord is built by taking a normal major chord, and adding on top of it the 7th note from the corresponding minor scale. E.g. for G7 we’d take a G major chord and add F, the seventh note in the G minor scale. For E7 we’d take an E chord and add the seventh note of the E minor scale, which would be D.

(PS You can always quickly work out which note is the minor seventh, because it’s always exactly two frets lower than the first note in your chord).

Most other chords tend to be either major or minor in quality, so the 7th chord’s slight mixture of the two is what makes them stand out.

Despite containing notes found in both the major and minor scale, we would still say the 7th chord is fundamentally major in character. This is because the minor note has been stacked on top of an already existing major chord, so the major quality prevails.

That’s the 7th part of the name and that’s what it means.

The #9 part takes the concept of mixing major and minor and takes it a step further by adding one extra note… a note that sorta shouldn’t be there.

To understand what is meant by that, we need to have a clear concept of a very important musical fact:

What makes a chord Major vs Minor?

What classifies and divides chords into major and minor is the distance between their first two notes.

All major and major-type chords have a distance of four frets (or four semitones) between the first note (root note) and the next note.

This gap – or interval – in this location is what actually gives the chord its major sound quality. We call this interval the major third.

The difference with minor chords is that their interval between the first two notes is smaller; specifically, one fret lower. All minor and minor-type chords have a distance of three frets (three semitones) between the root note and the next note. This interval is the minor third, and this is the difference that makes the minor chord sound minor.

A gap of one fret higher or lower. It might not seem like a big deal, but it’s a HUGE deal.

The type of third is what determines whether a chord is either major or minor.

Once a particular third is used, the major or minor-ness of the chord is set, and chords can’t be both. Or can they?

The 7#9 is both at the same time

The 7#9 chord is the addition of a minor third to a 7th chord. As a result it contains both types of third, making it both major and minor at the same time.

And this is the sound you’re hearing within the Hendrix Chord – a clashing and vibrant blend of the two tonalities of major and minor that shouldn’t work, but it really does. The fact that the minor and major thirds are only one fret apart makes it an extremely dissonant chord, but the fact that there is an octave in between them gives them enough sonic space between each other for the clash to sound cool.

On that note, there is no real such thing as “shouldn’t work” in music. It’s just a figure of speech. Any way you could possibly think to combine notes into a chord has already been done and is already understood.

The 7#9 is a type of extended chord, known as an altered dominant. An extended chord is one that is harmonised beyond the level of a 7th chord, i.e., 9th, 11th and 13th chords (a little more on this below).

An altered dominant is a dominant chord (meaning a 7th chord or a chord built from a 7th) whose notes differ from what they would naturally be in order to serve a specific musical purpose. Usually the purpose of using chord alterations is to increase tension, by setting up a dissonant note or two that demand to resolve into the next chord. This is how the 7#9 is often used in Jazz.

The classic use of the Hendrix chord isn’t really for any alteration purposes – it just sounds awesome! The best example I would give of the classic Hendrix chord sound, is probably Voodoo Child, which is essentially a vamp (i.e. a rhythmic one or two chord jam) with a home chord of Eb7#9. In the context of blues-rock, 7#9 sounds good by itself and sets up a perfect backdrop for mixing the major and minor pentatonic and blues scales in a solo. It’s like the Blues in a single chord!

Why is the minor third called #9 in the Hendrix Chord?

Understanding 9th Chords

A default 9th chord is the next step up the harmony ladder from a 7th chord. The simplest way to think of this is that all chords are built by stacking notes on top of each other with gaps in between them.

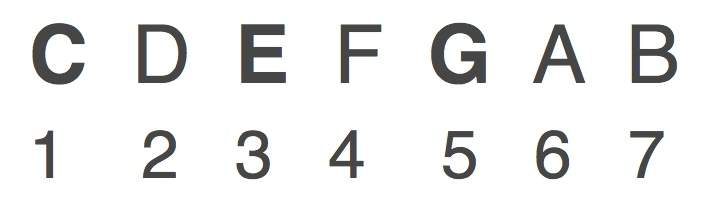

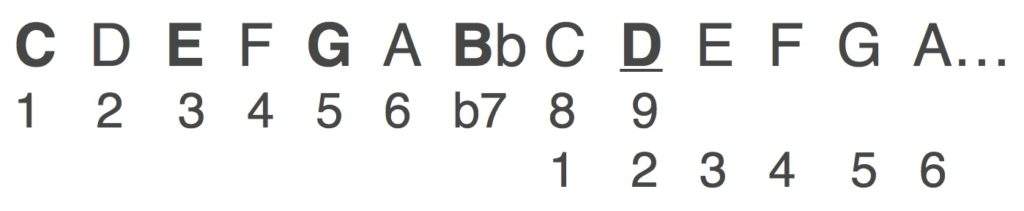

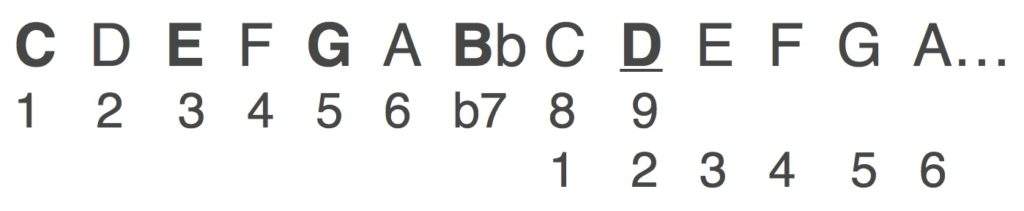

The major chord is constructed by combining the first, third and fifth notes of the major scale. For example, for C:

Giving us the notes C E G.

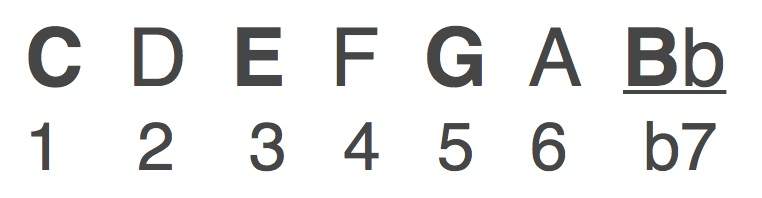

The 7th chord was created by taking the major chord as a base, then adding the seventh note from what would be the corresponding minor scale. We’ll label this note b7 for “flat 7” from now on, to indicate that it’s a borrowed note from the minor scale:

All the time we have moved in repeating steps or gaps called thirds. If we continue the process of stacking upwards through the same notes in the same sequence, we reach the beginning again and step into the same notes in the next octave:

The note we hit is the same as the 2nd note of the scale, which in this case would be a D. It’s easy to remember which is the 9th because it’s always two frets away from your starting note.

So a 9th chord is adding the 2nd note of the scale, but in this context we always call it the 9th. Why? Because we’re building on a 7th chord, and we’ve gone up through all the notes to get to where we are:

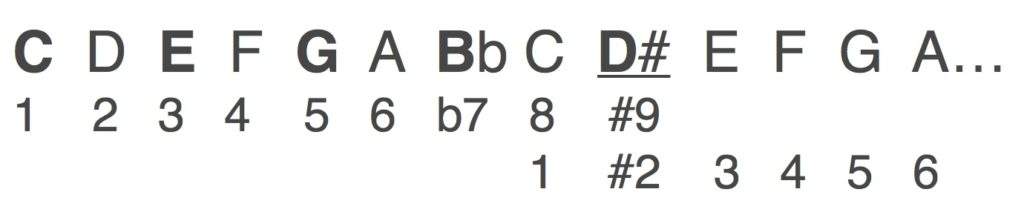

The #9 Alteration

This is how a 9th chord works, so a #9 just means a 9th chord as above but with the 9th (2nd note) sharpened by one fret:

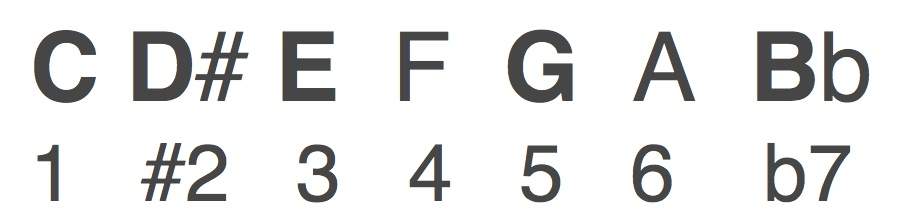

This means that the chord of C7#9 has the notes C E G Bb and D#. If we rearrange these in order of pitch:

It becomes easier to see that D# is three frets away from C, which is a minor third, and E is four frets away, which is a major third. This is why the chord sounds the way it does.

And there you have it – that’s how the Hendrix chord works, and why it has the name it does!

The Hendrix Chord is a great reminder of how many expressive tools are at your disposal with music. It can be something that inspires you to try out new chords and grow your palette of what sounds comfortable. It’s also a reminder that you really can play anything you want, and that nothing that sounds good “breaks the rules”. Always remember that music theory is not a set of rules there to constrain you – all it is there to do is show you how to understand the vast array of options you have, and help you to see how all notes can work together.

– Christy